Latest news

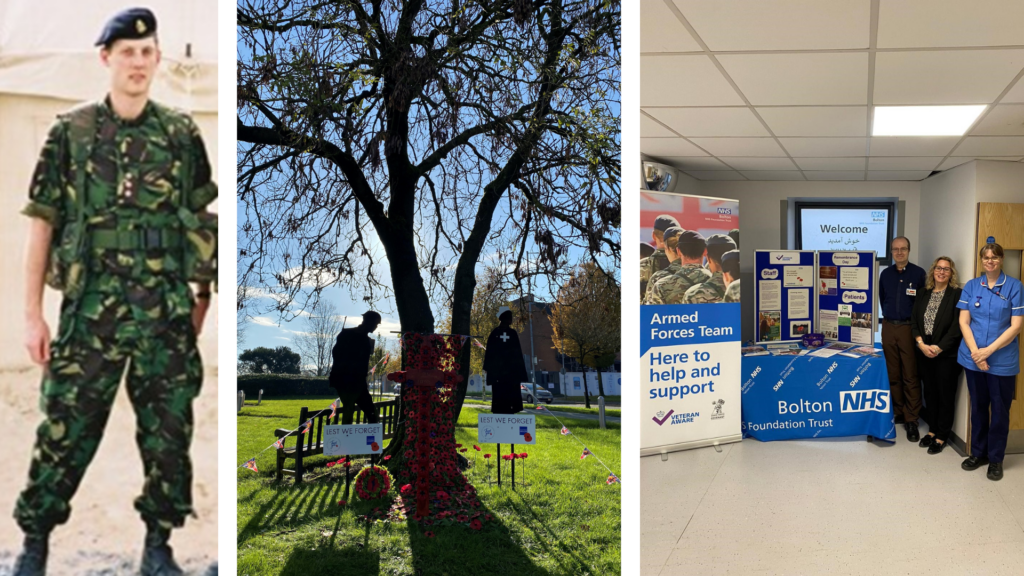

Former soldier turned consultant shares importance of recognising armed forces and veterans in healthcare

- Invite the local community to a remembrance service

- Step change in identifying veterans and armed forces personnel and providing support

- Veteran Consultant shares personal experiences to reach out to fellow veterans

The Trust are holding a Remembrance Service on Monday 11 November outside the Main Entrance at Royal Bolton Hospital.

The local community, staff, patients and visitors are invited to join the service at 10.50am followed by the raising of the Union flag, a two-minute silence and the Last Post.

As a Veteran Aware organisation, the Armed Forces team will have an information stand at the Main Entrance on Friday 8 November, for anyone who may have any questions around what support is available.

Dr. Simon Irving is a key member of the Trusts’ Armed Forces team and is also a Consultant and the Clinical Lead for Acute Medicine.

Over the last couple of years, Simon has been leading a step change within the organisation, in terms of supporting veterans and those in the Armed Forces community, whether they are staff members or patients and their relatives.

The campaign has seen the Veteran Aware reaccreditation for the Trust, along with introduction of Armed Forces and Veterans Information Packs, which includes vital information and support services and links to the Armed Forces Charity the SSAFA, counselling support and the Ministry of Defence.

Once a patient has been identified as a member of the armed forces community, this is recorded in the electronic patient records and appears on discharge summaries, improving communication with local GPs.

Veteran identification will feed through to any therapies assessment documents, opening avenues with additional support on discharge.

Simon said: “As a veteran, I’m fully aware that typically service personnel and veterans are reluctant to access any kind of mental health services.

“From my own personal experience, I know all too well the difficulties ahead and wanted to share my journey to give an insight to everyone or to reach out to anyone who can relate to it.

“I thought I’d start with a piece I wrote in 2014, which I think articulates why this is so important to me.

Even years on, talking about some of the more testing times in Iraq is difficult and stirs up a feeling of discomfort. It was a strange time. Some of the things I learnt out there, not least about myself, have been invaluable in my career and shaping who I am today.

“My feelings on treatment for returning soldiers are strong. There is the obvious argument for the physically wounded but, for me, the mental health side is the big concern.

“I never witnessed anything too unpleasant. Sure, I saw the results of warfare, with young men from Black Watch with amputations and the occasional post op trauma patient. I never saw my best friend step on an IED. I never saw a man trying to shoot me. I only really lived through a perceived threat.

It was strange, as a NHS doctor, being just 2km from the front line. Even stranger being just 500m from the artillery. The shelling began at prayer time each morning – maybe 4.30am, in order to cause maximum disruption and lower enemy morale. You can’t sleep through it, so you go out of your tent, put your helmet on and watch.

“Then there were the ‘gas, gas, gas’ alerts. Sitting in full Nuclear, Biological and Chemical (NBC) suits in temperatures over 40C, waiting for the all clear. It could take 90 minutes. I’d maybe try to read a book to distract myself, but all the time I couldn’t help wonder if the air around me was poisonous. I’d look at others for any signs.

“Then there was the way we were treated as reservists. To go into Iraq with my personal weapon, but no ammunition, down the main supply route (which was bring ambushed daily) felt wrong. This was because the Commanding Officer (from the Regular Army), felt that the TA couldn’t be trusted with ammunition.

“If, when in a war zone, I couldn’t be trusted with ammo, when could I be? Why was I being denied the equipment to defend myself. The whole time I was out there, I was given no desert kit. I had to return the ceramic plates in my body armour to give to those on the front line, due to lack of supplies.

“Why do I say all this? When I returned home, I had a bit of a tough time. I had counselling, which was invaluable. I paid for it privately. Why would I approach an army counsellor, when my issues were with the army? Why, initially, did I feel reluctant to seek help?

“My experiences were minor, in the grand scheme of things, so what justification did I have to feel like I needed help? Service personnel are expected to cope and there is a stigma surrounding mental health. Does the machismo of the Armed Forces lead to a reluctance to report symptoms? It took several months for my sleep pattern to return to normal and after that I would still wake up with a sense of unease.

Those who choose to serve their country sign up and understand the risks to life and limb. They understand that they may see things that no one should have to see.

“People cope with things in different ways and some people need help with that. The rates of alcoholism, drug abuse and suicide in returning soldiers demonstrates that more needs to be done. This cannot be just any counsellor, but someone with the skill and experience of dealing with the unique issues around war.”

If you would like to know more about the support services offered to veterans and the armed forces, please email ArmedForces@boltonft.nhs.uk.